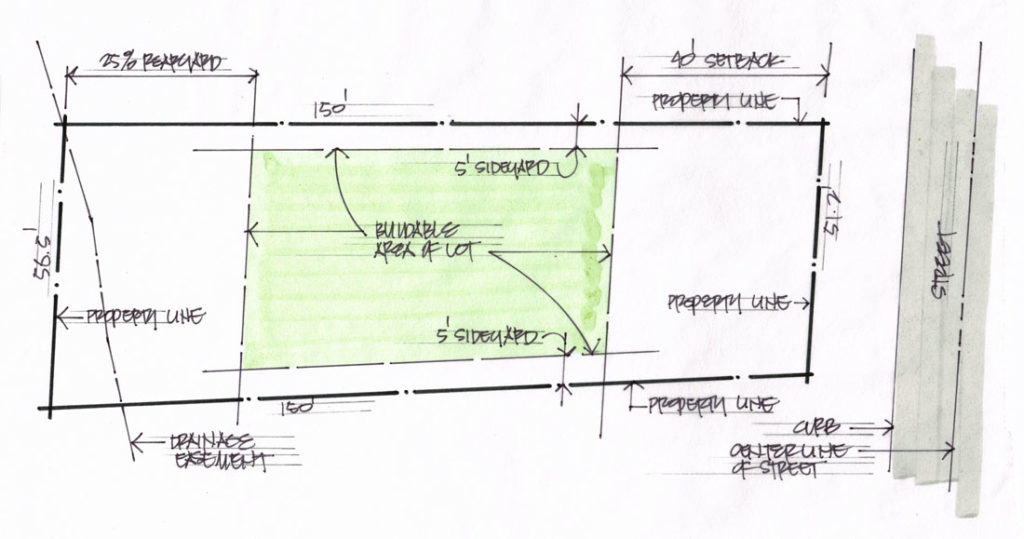

Municipalities enforce all kinds of restrictions on what you can build on a property and where you can build it. Sideyards, rearyards, building lines, easements, right of ways, and no-build zones are collectively called “setbacks” and determine how close to your property lines you can build a house, and together, define the “buildable area” of the lot.

Each restriction serves a different purpose, and you should know how all of them affect your property before you start planning a new home or room addition project.

Cities want the fronts of all the houses on a street to line up, more or less, so that one house doesn’t block the views of the others (and because planners like uniformity). And in suburban settings, they usually want everyone to have greenspace between the street and the house.

That’s enforced with a front setback – also called a building line – the distance the front of your house must be “set back”, usually from your property line.

But not always. Building lines are sometimes measured from the curb, sometimes from the center of the road, and sometimes from the city’s right-of-way (more about ROWs later). In most subdivisions I’ve worked in, building lines are 20 to 40 feet back from the front property line.

In some newer subdivisions, cities have begun establishing “build-to” zones, which amount to flexible building lines. Build-to zones keep house fronts from lining up too perfectly and (hopefully) add a little more variation along the street.

Sideyard setbacks keep houses from getting too close to each other, and are the restrictions that cause homeowners the most headaches. My office takes frequent calls from people who want to add a little space to the side of their house – often another garage bay – only to discover their sideyard limits won’t allow it.

How sideyards are measured is often determined by the age of the lot. In older lots, sideyards are usually a fixed number – five or ten feet from each side property line, for example.

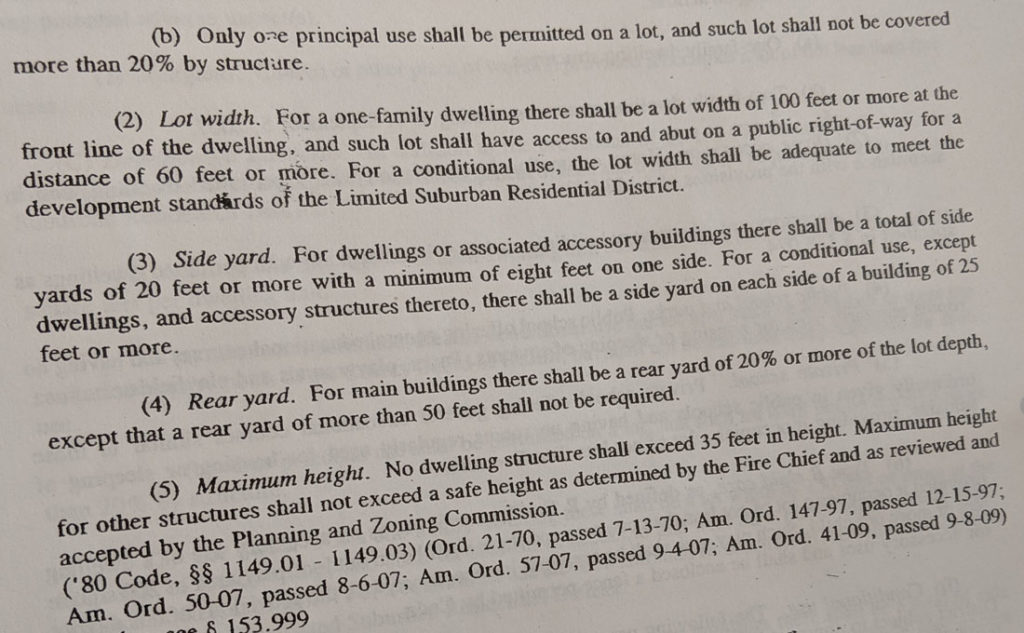

In newer areas, sideyards are often measured as a percentage of the lot width, with a minimum sideyard dimension on one side. So a 100-foot wide lot might have a total sideyard of 20 percent with a minimum sideyard of 8 feet on one side. That means one side of your house can be as little as 8 feet from the property line, but the other side must then be at least 12 feet from the opposite property line.

That’s easy math on a rectangular lot with parallel property lines. On irregularly-shape lots, things get more complicated.

One older subdivision I work in frequently has no sideyard setbacks at all – instead, they enforce a minimum distance between structures. That formula can cause friction between neighbors, though, since the guy who builds first determines the “setbacks” for the adjoining properties.

Like a front building line, a rearyard setback determines how close you can build to your rear property line. Rearyards in subdivisions make sure everyone has some usable backyard, and provide a “green corridor” within the block.

Sometimes rearyards are fixed distances, and sometimes they’re a percentage of the lot depth with a fixed maximum. Many of the properties I work on have rearyards of 25 percent.

Now you can begin to see how these restrictions affect your property. On a 150 foot deep lot, a 25 percent rearyard takes up 37.5 feet. Add a front building line of 30 feet and you’re left with 82.5 feet, or about 55 percent of your lot depth to build on.

In urban areas with rear alleys and detached garages, the garage is typically allowed to be built between the rearyard line and the rear property line, close to the alley.

But wait, there’s more.

These are areas, usually at the back of a lot, where no construction of any kind is allowed. In some municipalities (like mine), that includes things like swingsets, firepits, and play forts.

No-build zones are usually created to protect natural features like stands of trees or ravines. Most of the time they’re small enough that they’re within the rearyard setback of the lot, but they do eat up some of your usable backyard space.

Fortunately, no-build zones are fairly rare, but it’s still worth checking to see if one exists on your property.

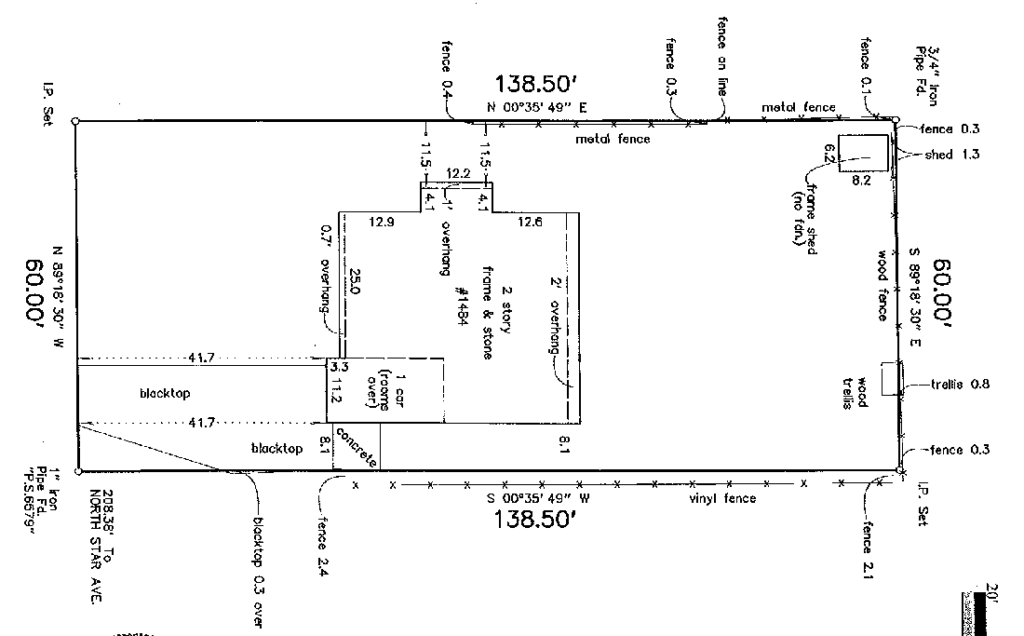

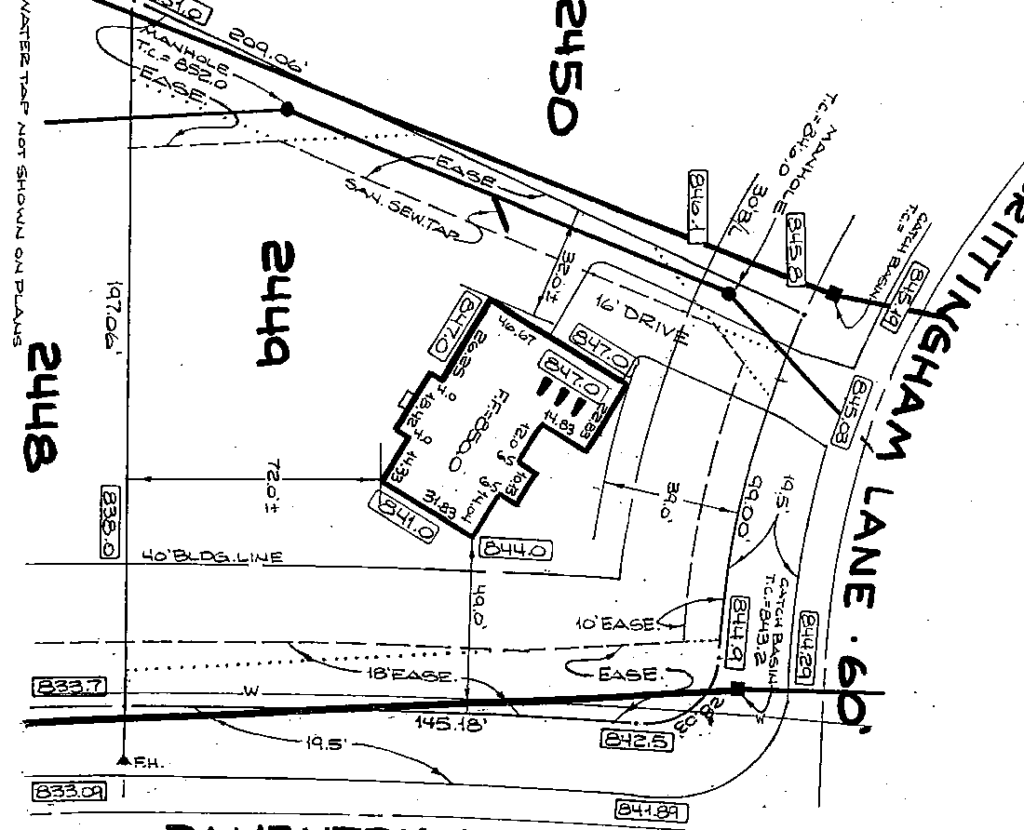

Easements are different than all of the other setbacks I’ve described above, because they can occur anywhere on a property. An easement grants permanent access across your property for a variety of specific uses.

The most common type of easement is a utility easement, where access is granted to a utility company to maintain their underground (usually electric) lines, or to the city itself to maintain underground sanitary or storm sewers.

Utility easements are usually centered over the utility line, and are wide enough to allow the passage of maintenance equipment – often 10 or 15 feet wide.

Here’s the kicker, however. Even though that storm sewer line is 20 feet deep, you can’t build anything in the easement above it. That’s not a big problem when the line is below a side property line, and within the sideyard setback. But when it cuts through the middle of a property, as they sometimes do, it can severely limit the buildable area on your lot.

Other types of easements include drainage easements and driveway easements, where a land-locked property is granted an easement over an adjacent property with access to a public street.

Private easements can also be made between property owners, or between homeowners and community associations for bike and walking paths.

A right of way is similar to an easement, but is usually associated with a public street, giving the public the “right of way” over the part of private property directly adjoining the street.

Like an easement, a right of way gives city crews the right to cross onto your property to maintain the streets and sewers. And when a public sidewalk crosses your land, it gives the public access, too.

As I said at the beginning of this article, knowing how setbacks affect your property is a critical first step in most home design and room addition projects. You don’t want to get deep into a design solution only to find out there’s no room to build it.

Unfortunately, all this information isn’t always easily accessible, or even available at the same place. But a little research and a phone call or two should uncover everything you need.

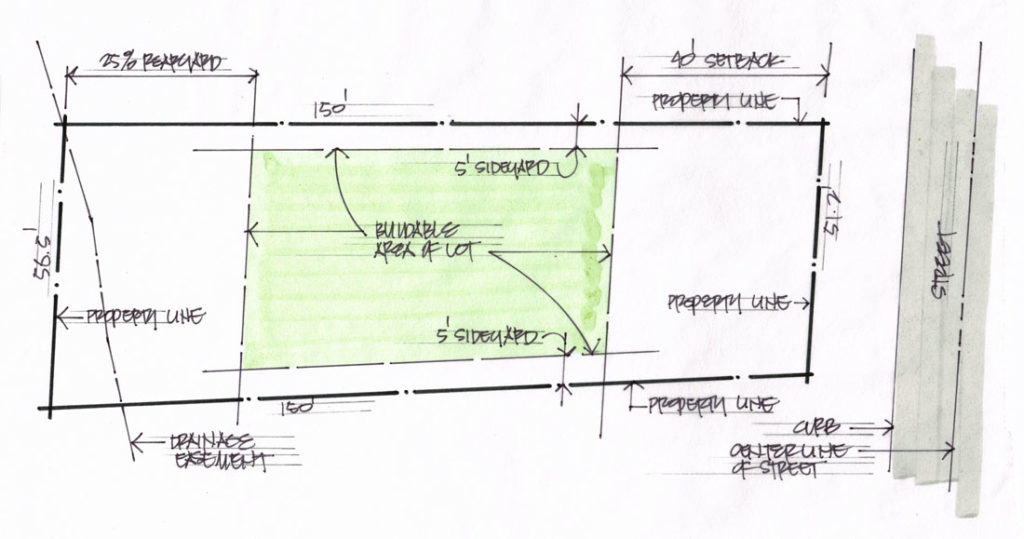

The first place to start – assuming you already own the property – is the file with your closing papers in it. Somewhere in there is a mortgage survey, ordered by your lender to describe the property.

A mortgage survey shows the length and orientation of the property lines, and the location of any buildings on it. If there’s a house on the lot, it should show the distance between the sides of the house and the side property lines.

If you’re lucky, it may also show the front yard setback (building line) and may show rights of way and utility easements. But not always.

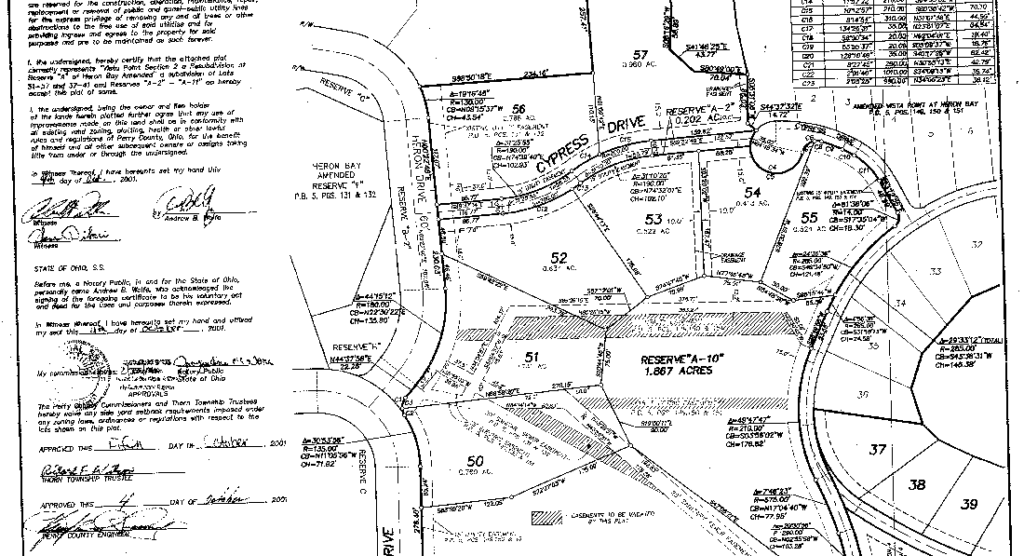

That information will be on the recorded plat. A plat is the document that officially creates the property and establishes building lines and easements – at least the ones in force at the time. Since it’s a public document (that’s essentially what “recorded” means), a phone call to the city planning department or city engineer should get it in your hands.

A note of caution, however – plats are fairly complicated documents sometimes covering several pages of drawings. Get a professional to help you read and understand it.

If all of the sideyards, setbacks, and easements are on the plat, you’re done. But when they’re not, you’ll need to reference two more documents. One is your local zoning code, which will describe the required setbacks, depending on the size of the lot.

The other document is the site engineering drawing for your neighborhood. This should include the location of all of the underground utilities that were installed when your street was built.

Finally, a neighborhood with a homeowner’s or community association (HOA or COA) may have additional restrictions in place (there may be additional setbacks from golf courses and other community facilities, for example). Give ’em a call and ask.

Sounds like a lot of work, doesn’t it? It can be – but whether you uncover unknown restrictions on your land, or just get peace of mind that you can build where you want, it’s always worth the effort.

Contact me to learn more about the services I offer and how I can help make your new home or remodeling project exciting, valuable and unique.